Site Directory.

Hello, and welcome to my site! This blog is primarily about parrots, and contains several articles I have written for various parrot magazines, primarily Parrots. A couple things were also written specifically for this blog, and I also post interesting news stories about parrots and other birds as I find them.

Please click HERE if you would like to go to a directory of the site with a list of all the posts I’ve made. There are articles about wild parrots, caring for captive parrots, and parrot behavior, along with news articles about parrots.

Click this link to read more about me and my animals: About the Author

Peggy, my Jenday Conure

The Extraordinary Eclectus Parrots of the Cape York Rainforest

Note: This is an article of mine that was previously published in “Parrots” magazine.

I recently traveled to the Cape York Peninsula of Australia to view its fascinating landscapes and wildlife. I chose to include this location on my itinerary because it is home to several bird species I have long wanted to see in the wild, including the Black Palm Cockatoo (which I wrote about in a previous issue) and the Eclectus Parrot.

Eclectus parrots have a very limited range on mainland Australia and only occur in rainforests in the Iron Range National Park on the east part of the Cape York peninsula. The subspecies that occurs there is called Eclectus roratus macgillivrayi, and it is the largest of all of the Eclectus subspecies, of which there are nine. Eclectus parrots also occur on the island of New Guinea and its surrounding islands, the Solomon Islands, Sumba, and the Moluccas Islands.

I find Eclectus parrots fascinating because their breeding behaviour and color patterns are very different from those of most other parrots. Unlike most other parrot species, male and female Eclecus are completely different colours. The males are a vibrant emerald green while the females are a dark ruby red, usually with a vest of violet or cobalt feathers. The two sexes are so different that it wasn’t immediately apparent to western biologists that the males and females belonged to the same species.

There are other parrot species that have males and females that look different, (are sexually dimorphic) but none show such extreme colour differences between the sexes. For instance, mature male Ringneck Parakeets (Psittacula krameri) have a black ring around their necks while the females do not. Both, however, are green (at least in wild populations – different colours exist in captive birds). And, in most sexually dimorphic parrot species, males do not develop their adult plumage until they have molted a few times. For example, male ringnecks do not develop their rings until they are at least 18 months old. Eclectus are different in that the chicks are very easy to sex as soon as their feathers start appearing: boys are green and girls are red.

The form of sexual dimorphism seen in Eclectus Parrots is strange even when they are considered against all other bird species. It is not unusual for male birds to be much more extravagant looking than females – peacocks are the perfect example of this – but in the Eclectus, neither sex is really more colorful than the other, although it’s the female who would stand out more in nature due to her red colouring. Males would blend in well against green, leafy tree tops.

I went to the Cape York Peninsula with a birding group, and all of us wanted to see both male and female Eclectus parrots. The photographers in the group were very keen to get pictures of them as well. We frequently observed males flying high over the rainforest canopies, but finding females took more effort. Our guide did know the location of an Eclectus nest hole, which was at least 25 m up a large tree. Due to the distance, we needed to use a powerful spotting scope to see the nest hole’s owner. After a period of searching with binoculars and the spotting scope, we located a female perched close by. It wasn’t the right time of year for Eclectus to be breeding, but that doesn’t matter, as breeding female Eclectus will stick around a claimed nest hole for all or most of a year.

Eclectus Parrot Nest Cavity

Female Eclectus

When we came back to the nest hole another day, we found more Eclectus. We initially found a female and waited with the hopes of seeing males. Our patience was rewarded, as more than one male eventually came to visit the female. We also eventually saw another female show up nearby as well. What a great sighting! I managed to get a few photos but it was tricky as the birds were very high in the trees and numerous branches were in the way. Thus, my pictures aren’t the highest quality, but I’m just happy that I was able to view these birds. The females were easier to see and photograph than the males, who moved around a lot more.

Female and Male Eclectus

Seeing more than one male attend to a female is not unusual for Eclectus parrots on the Cape York Peninsula. Most parrot species are monogamous, but Cape York Eclectus are polygynandrous, which means that a female may mate with multiple males and a male may mate with multiple females. Studies have shown that female Eclectus parrots on Cape York may be courted and fed by up to seven males at once. Males are not monogamous either and will sometimes court and feed more than one female. In one instance, a male had young with two females situated 7.5 km apart. Given that the male must provide food for the female and young, he must have been very busy. That males do most of the foraging explains why all the Eclectus I saw commuting over rainforest canopies were male.

Female Eclectus Parrot

There are other bird species where females will mate with more than one male, although the behaviour of Eclectus is very different from the behaviour of these other polyandrous birds. In most polyandrous birds (such as phalaropes and some sandpipers), the male will care for the young while the female finds another mate. In such species, it is often the female that is the more colorful sex, so the sex roles are essentially reversed. However, this is not so in the Eclectus, because the female will guard the nest hole and her young while multiple males will feed her. She will then feed any nestlings present, and the male(s) will feed the young once they have fledged. The female does not abandon the eggs after they are laid as do the females of many other polyandrous bird species.

Why are Cape York Eclectus parrots polygynandrous? On Cape York, the sex ratio of adult Eclectus parrots is biased towards males, so there simply aren’t enough females for each male to have a mate. However, in many bird species, if a male cannot find a mate, he may simply go without one and live as a bachelor. In other birds, young birds who cannot find a mate may stay around and help their relatives – usually their parents – raise young. This is because natural selection shapes animals to act in ways that help them pass their genes on to a new generation. Of course, an animal can do this by bearing young, and its genes will be passed along through them. However, an animal can also propagate its genes by helping its parents raise more of its siblings. This is because identical copies of half of any animals’ genes are also present in their siblings because they share the same parents. The theory that animals can pass their genes on by helping close relatives produce more young is called “kin selection.” In many bird species, young birds who cannot find a territory or mate will often stay with their parents and help them care for young. The presence of these helpers often increases the number of young a pair can raise, and the helpers also benefit by gaining valuable experience in caring for young.

However, genetic studies on Eclectus parrots conducted on the Cape York Peninsula have shown that males are generally not closely related to the females they court. So, kin selection does not explain why more than one male may court and feed a single female. There must be another reason for this odd behaviour.

The Eclectus’ unusual breeding behaviour is the result of a sex ratio that is biased towards males, along with a shortage of suitable nest holes. Young females have a higher mortality rate than males, so there are simply more males out there than females. There are also females that may not be able to breed because they cannot find good nest holes. Good nest holes are rare, because it is not simply enough for an Eclectus to find a tree with a hole in it. It must be one that either does not flood during rainstorms or one that dries out quickly because Eclectus chicks can easily drown if their nest hole becomes flooded. Eclectus usually nest in holes that have entrances that face sideways, rather than straight up. The nesting hole that I saw on Cape York was ideal for Eclectus to raise young in because it faced sideways. The lack of quality nesting holes means that there can not be enough females with nest holes for every male, so each female ends up with more than one partner.

The fact that multiple males may mate with any one female means that, in any given season, there is a good chance that a given male Eclectus will be helping to raise young that he did not father. However, a male Eclectus needs to court a female, even though she may have other suitors, if he is to have any offspring. As time goes on, he will become more likely to actually father young. This can take years because some males are far more successful than others in fathering young, but a male that doesn’t try to court a female will never have offspring. Some male Eclectus will also mate with more than one female to increase their chances of fathering young.

The different roles that male and female Eclectus have in raising young actually appears to explain why they are coloured so differently. Australian biologists have studied the colors in male and female Eclectus Parrots by taking optical measurements of the birds and their surroundings using a spectroradiometer. This instrument measures various properties of the light reflected or emitted off of objects. It was important to make objective measurements using such an instrument because parrots do not see the world the way humans do. Parrots can see light into the ultraviolet spectrum, which is invisible to people. This means that an object which blends in with its environment to a person may actually be very conspicuous to a parrot.

The optical measurements indicated that male Eclectus, with their largely green plumage, blend in well with the leafy treetops they forage amongst. This makes them inconspicuous to the raptors that prey on them. Males spend several hours each day foraging because they need to feed not only themselves, but a female or two, and possibly some newly fledged young. Females do not have as large a need to be camouflaged, since they spend most of their time in or near a nest hole they can hide in should a predator show up. Additionally, the females actually do need to be quite conspicuous at times. They must compete for nests with other Eclectus and with Sulphur-crested Cockatoos, who often take over Eclectus nests. Female Eclectus will display outside their nests by calling and drawing attention to themselves, and their colour makes them stand out very well against a leafy canopy. By being very conspicuous, a female can let other parrots know that her nest hole is taken and that they should stay back. This often works to prevent conflicts, but even so, females still sometimes have to fight off intruders, primarily other parrots. Fights between Eclectus can be very intense; and even fatal. This makes me wonder if one of the female Eclectus I saw outside of the nest hole was a youngster, because a female is unlikely to tolerate the presence of another adult female outside her nest hole.

The spectroradiometer measurements revealed another aspect of Eclectus biology that would have remained a secret had not such an instrument been used. While male Eclectus are difficult for predators to see against green leaves, they are quite conspicuous when seen by other parrots outside of a nest hollow. Green does show up well against a brown tree trunk, but the measurements from the spectroradiometer showed that an Eclectus’ feathers also reflect ultraviolet light that other parrots can see but that humans and many of the Eclectus’ predators cannot. So, while Eclectus look brilliant to people, they look even more brilliant to each other.

Eclectus parrots are truly extraordinary birds. Their unusual form of sexual dimorphism and non-monogamous breeding system appears to be the result of their having evolved in an environment where they have to compete with other birds for suitable nesting holes. Seeing them in the wild was a thrill I will never forget.

References

Heinsohn, R., Murphy, S., and Legge, S. 2003. Overlap and competition for nest holes among eclectus parrots, palm cockatoos and sulphur-crested cockatoos. Australian Journal of Zoology, 51, 81-94.

Heinsohn R., Legge S., and Endler J.A. 2005. Extreme reversed sexual dichromatism in a bird without sex role reversal. Science, 309, 617–619.

Heinsohn R, and Legge, S. 2003. Breeding biology of the reverse-dichromatic, co-operative parrot, Eclectus roratus. Journal of the Zoological Society of London, 259,197-208.

Heinsohn R., Ebert, D., Legge, S., and Peakall R. 2007. Genetic evidence for cooperative polyandry in reverse dichromatic Eclectus parrots. Animal Behaviour, 74, 1047-1054.

Heinsohn R. 2008. The ecological basis of unusual sex roles in reverse-dichromatic eclectus parrots. Animal Behaviour, 76, 97-103.

Legge, S., Heinsohn R., and Garnett, S. 2004. Availability of nest hollows and breeding population size of eclectus parrots, Eclectus roratus, on Cape York Peninsula, Australia. Wildlife Research, 31, 149-161.

Marshall, R, and Ward. I. 2004. A Guide to Eclectus Parrots as Pet and Aviary Birds, (revised edition). ABK Publications. South Tweed Heads, NSW, Australia.

The Black Palm Cockatoos of the Cape York Peninsula

Note: This is an article I wrote about Black Palm Cockatoos for “Parrots” magazine.

The Black Palm Cockatoos of the Cape York Peninsula

By: Jessie Zgurski

The Black Palm Cockatoo, with its striking appearance and regal demeanour, is a bird guaranteed to turn the heads of parrot-lovers. Black palms are the largest of the cockatoos, and their long, loose, crests and bright red facial patches give them a very dramatic look. Their behaviour is dramatic as well, as they use branches as drumsticks in their territorial displays. They are rare in captivity, especially in North America, and to view them in the wild, one must venture to the island of New Guinea or Australia’s Cape York Peninsula.

I recently traveled to Australia to view its wildlife and explore its more remote and wild landscapes. I chose to include the Cape York Peninsula in my itinerary, as it is home to parrots and other birds that I have long wanted to view in the wild. The Peninsula is also a wonderful place for people like myself who appreciate unspoiled wilderness, as it is sparsely populated and covered in rainforests, woodland savannahs, wetlands, and heathlands. It also has miles of pristine beaches, coastal mangrove forests, and river systems, all filled with fascinating wildlife.

The Cape York Peninsula is in the far northwest of Australia, with its tip being the northernmost point of the continent. Black Palm Cockatoos can be found there north of the Archer River, and they are the only black cockatoo whose range extends outside of Australia, as they also occur in the lowlands and foothills of New Guinea, the Aru Islands, and other off-shore islands of New Guinea. The Cape York Peninsula was once connected to New Guinea, and the two places therefore share many aspects of their flora and fauna.

I saw Black Palm Cockatoos in the Iron Range (Kutini-Payamu) National Park, which is on the east side of the Cape York Peninsula. Iron Range is an excellent place for birders, as it is the only place in Australia where many gorgeous species, including Eclectus and Red-cheeked Parrots, can be found. Getting there can require some planning, as it is in a remote location that can be unreachable by car during the wet season due to flooding. I went there with a birding tour group during the dry season, when all roads were open. A large proportion of the other people we encountered in the park were also birders, and we exchanged birding tips and sightings with many of them.

In Australia, Black Palm Cockatoos prefer to live in landscapes characterized by a mosaic of closed, dense rain forests, and open, dry woodlands. Iron Range has both, making it an ideal place to view these cockatoos. The rainforests grow where soils are moist, and they are lush and dense, with little sunlight reaching the ground. The trees in Cape York rainforests can grow up to 35 meters high and many are draped in thick vines and have other plants growing on their bark. Walking through the rainforest isn’t always easy, as the ground can be covered in vines, thick tree roots, and decaying vegetation. The dense canopy of the Cape York rainforest makes spotting birds a challenge, but the rewards are worth it, as the birds are spectacular, and include two species of Birds of Paradise, Eclectus Parrots, and colorful forest kingfishers. There are also species that can be found near the ground as well, such as Australian Brush Turkeys.

Australian Rainforest

Woodlands are found where the soil is drier, and they typically have open canopies, making them much sunnier places than the rainforests. As a result, the understory is usually covered in thick grass. Lizards are common in the woodlands and can usually be seen basking in the sun in open areas. Birds can be easier to spot in this environment as well, and I saw numerous Sulphur-crested Cockatoos in the woodlands, although they venture into the rainforests as well.

Woodland habitat in Iron Range National Park

Black Palm Cockatoos in Australia prefer to nest in woodlands that are close to rainforests, although in New Guinea they often live and nest in large tracts of pure rainforest. Like other cockatoos, Black Palm Cockatoos nest in tree cavities, which they fill with sticks to a depth of about 2 m. The sticks help with drainage.

Breeding season for Black Palm Cockatoos in Australia occurs from August to February. It gets very rainy on Cape York at this time, so upward-facing nests in tree snags must have good drainage or chicks can drown. Finding a suitable nest hole is a challenge for Black Palm Cockatoos. They must compete with other birds of their own species for nest sites, as well as with Sulphur-crested Cockatoos. Eclectus Parrots also need large tree cavities to nest in, but on Cape York, they typically nest in rainforests and tend to nest in different tree species than do the palm cockatoos

In Australia, Black Palm Cockatoo males will advertise their presence around nest holes with an impressive display that includes calling, whistling, bowing, wing spreading, and drumming. Males will take a branch, strip of bark, or hard seed pod, and use it as a drumstick. They will also sometimes drum on their perches with their bare feet. These drum displays may be territorial displays, but they also seem to have a courtship function, as they are often directed at females, who pay close attention to them. Different males often produce different beat patterns, and individual males can have favored beats. The duration of a display can range from two to 100 beats.

I was very lucky in Cape York, as I saw a male Black Palm Cockatoo perform a drumming display. He was not on a nesting tree and was accompanied by two other adult cockatoos, so he was likely a young male practicing his drumming. I watched him as he stripped a hard piece of bark from a eucalyptus tree, held it in his foot, and then banged on the tree branch he was standing on with it. All the while he called, whistled, and swayed his shaggy crest. I was absolutely mesmerized by this wonderful bird and his display.

Black Palm Cockatoo

Black Palm Cockatoo, drumming and calling.

At the start of breeding season, male palms in Cape York may perform their displays around multiple nest holes, although in the end they will use only one. Males sometimes fight each other for access to nest holes, and these fights can involve growling and feather pulling. Palms may also get into similar conflicts with Sulphur-crested Cockatoos. Sometimes, birds of both species will claim the same nest. Biologists have observed Sulphur-crested Cockatoos removing sticks from a nest hole that a Black Palm Cockatoo had placed there. Once the two birds meet, the palm will usually chase off the sulphur. It is rare (but not unheard of) for a Sulphur-crested Cockatoo to take over a Black Palm Cockatoo nest site.

Sulphur-crested Cockatoo

Black Palm Cockatoos are monogamous and have very low reproductive rates. Pairs usually produce one egg per clutch, with males and females sharing incubation, and they do not breed every year. In one study done on the Cape York Peninsula, biologists monitored 28 active nests, and found that each pair’s chance of successfully fledging their young was only about 25%. This low reproductive success rate was due to egg infertility (17.2% of eggs affected), predation of eggs (24% of eggs affected), and predation of nestlings (37.9% of nestlings affected). The major nest predators included monitor lizards, Giant White-tailed Rats, Amethystine Pythons, and butcherbirds.

A pair of Black Palm Cockatoos

Despite this, Black Palm Cockatoos are not currently considered endangered on a global scale, which indicates that they must have lifespans of several decades. Without such long lifespans, most pairs wouldn’t be able to replace themselves and the species would eventually decline into extinction. This hasn’t happened, and Black Palm Cockatoos are currently listed as “Least Concern” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. However, chicks are hunted for meat or poached for the pet trade in some parts of New Guinea, and in Australia, dry-season woodland fires can reduce the abundance of suitable nesting trees. A slow-breeding species such as this cannot rebound easily after disasters have decimated populations, which means that major land-use changes that affect their habitat could easily push them towards a vulnerable status.

Although Black Palm Cockatoos are famous for their unique drumming displays, they also have a complex and sometimes unusual vocal repertoire. Their vocalizations include the typical loud parrot squawks, along with whistles and a greeting call that sounds like they are saying the word “hello.” Their vocalizations include contact calls, flight calls (including a call used only during landing), nestling begging calls, and a distress call. Nestlings also produce a unique vocalization while they are being fed, and fledged juveniles have a unique call that sometimes causes an adult to feed them. Pairs will also duet with each other, where they vocalize simultaneously or alternately with each other.

Palm cockatoos also produce a “crack” call during fights and some non-aggressive interactions. Consecutive “crack” calls appear to function as an alarm that warns other cockatoos of a potential predator. Palm cockatoos also produce a variety of other complex vocalizations that may function in territorial defence.

Their loud whistle calls and various squawks can help birders locate palm cockatoos. To find them, the birding group I was with drove slowly along the roads running through the woodlands in Iron Range. It didn’t take long to find a group of three birds this way. We also ran into more groups while searching for other birds. Black Palm Cockatoos tend to occur in pairs or trios (a pair and their offspring), and sometimes in small groups. However, they do not form huge flocks of 100 or more birds the way some cockatoos (like Galahs, Sulphur-crested Cockatoos, or Bare-eyed Cockatoos) can. Black Palm Cockatoos are usually located in trees, but we did find a small group near a beach feeding on the ground on fallen palm fruits.

I was absolutely thrilled to be able to see these intriguing and unique cockatoos in the wild. Not only that, but I was able to see a male perform his drum display. Black Palm Cockatoos are the only animal known to use a tool to produce sounds, as birds that use tools typically use them for foraging purposes. The Cape York Peninsula is also home to another unusual parrot species, the Eclectus Parrot. Eclectus parrots were more challenging to see. However, I managed, with a lot of looking upwards, to view a group of males and females. I will write more about these fascinating parrots in an upcoming article.

REFERENCES

BirdLife International. 2016. Probosciger aterrimus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22684723A93043662. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22684723A93043662.en. Downloaded on 01 January 2018.

Forshaw, J. M. 2002. Australian Parrots, Third (Revised) Edition. Avi-Trader Publishing, Robina, Queensland, Australia.

Heinsohn, R., Murphy, S., and Legge, S. 2003. Overlap and Competition for Nest Holes among Eclectus Parrots, Palm Cockatoos, and Sulphur-crested Cockatoos. Australian Journal of Zoology 51: 81-94.

Heinsohn, R., Zeriga, T., Murphy, S., Igag, P, Legge, S., and Mack, A. L. 2009. Do Palm Cockatoos (Probosciger aterrimus) have long enough lifespans to support their low reproductive success? Emu 109: 183-191.

Heinsohn, R., Zdenek, C. N., Cunningham, R. B., Ender, J. A., and Langmore, N. E. 2017. Tool-assisted rhythmic drumming in palm cockatoos shares key elements of human instrumental music. Science Advances 3:e1602399.

Zdenek, C.N, Heinsohn, R., and Langmore, N. E. 2015. Vocal complexity in the palm cockatoo (Probosciger aterrimus). Bioacoustics 24: 253-267.

Australia Trip: Lakefield and Musgrave Area

Today, I’ll post more of the pictures I took on my Australia trip. These ones are from the Musgrave and Lakefield area in northern Queensland.

Red-winged Parrot

The above parrot is a young Red-winged Parrot from Lakefield National Park. The adult males and females of this species are not difficult to tall apart, as the males have bright red and black wings, while the females have green wings with a bit of red on them. Young males look like females until they are about two.

Rose-breasted Cockatoos

These Galahs (or Rose-breasted Cockatoos) were in a pasture close to the Musgrave Roadhouse. A large flock also foraged on the grass airplane runway there as well. There were probably a few hundred of them around. Galahs are quite common around agricultural areas in Australia, as they feed on grains and will drink out of livestock watering holes.

Rose-breasted Cockatoos (Galahs)

As the sun started to set, numerous Galahs would gather in the trees to roost together. They all call to each other, making this a rather noisy affair.

Rose-breasted Cockatoos (Galahs)

More Galahs.

Sulphur-crested Cockatoo

Sulphur-crested Cockatoos were common where ever I went. I saw this one at Archer River, near the roadhouse. These cockatoos seem pretty flexible in their eating habits and would feed on the ground or in trees. Throughout this trip, most sulphurs I saw were alone or in pairs, but they can occur in very large flocks.

The other parrots I saw in this area included Rainbow Lorikeets, Golden-shouldered Parrots, and Pale-headed Rosellas. My camera wasn’t working the day I saw those, which is unfortunate, because I got some very good views of the Golden-shouldered Parrots. They are beautiful birds – the males are turquoise and crimson, with golden feathers on the bend of the wings, with the females being green and turquoise. Unlike most other parrot species, they do not nest in tree hollows, but instead nest in termite mounds. They are an endangered species, with about 1,300 individuals let in the world.

Nankeen Kestrel

Termite mounds in Australia can be quite large. The above photo shows a Nankeen Kestrel perched atop a termite mound

Rainbow Bee-eater

This is one of my favorites of the bird pictures I took in Australia. This is a Rainbow Bee-eater, and they were quite common in Lakefield National Park. As the name suggests, they do indeed eat bees (along with other flying insects),

Rainbow Bee-eater

Rainbow Bee-eaters forage by waiting on a perch for insects to fly by. They will then fly out, capture an insect, and fly back to the perch to consume it. They will rub the stingers off of bees or wasps before consuming them.

Quite a few finches that are commonly kept as pets can be found in Australia. The above photo shows a pair of Owl Finches getting a drink of water.

These are Star Finches. The birding group I was with came across a flock of about 50 of them. They were in some shrubs around a small, shallow pond, with all the birds seemingly taking turns to go down to get water.

We also found these Black-throated Finches (AKA Parson Finches) around the same pond. Note the bee-eater on the left as well.

Rainbow Lorikeets, birds of Cairns (Australia), and Twitter

Today’s post features photos of the birds I saw while I was in Cairns, Australia. I primarily birded around the botanical gardens and the waterfront area (Cairns Esplanade).

Also, if you have a twitter account, you can follow me at: https://twitter.com/Ft_Mc_Biologist

I primarily plan to post wildlife pictures I have taken, many of which will feature parrots.

Rainbow Lorikeets were very common in the Cairns area. They were usually present in groups and they are very colorful, active and noisy. There’s a group of trees downtown they like to roost in, and as the sun sets, hundreds of them gather in these trees and make an incredible amount of noise.

I saw the above birds downtown. They stayed upside down like that for a while and beak sparred with each other.

Lorikeets consume a lot of nectar and the bird above is licking nectar off of some flowers. Lorikeets have long, brushy tongues that allow them to maximize the amount of nectar they can get, and that allow them to reach deep into long flowers.

A lot of nectar-feeding birds simply lap up nectar and pollen without destroying flowers. Lorikeets, on the other hand, can be destructive at times. I took the above photo at the Cairns Botanic Garden. This mess was created by a flock of Rainbow Lorikeets feeding on flowers in a tall tree. The bird on the ground picking through the mess is an Australian Brush Turkey.

Here’s one of the lorikeets that was contributing to the mess. These birds were quite high up so the pictures I took of them aren’t great. Rainbow Lorikeets were (I think) the only bird I saw every day on my trip to Australia.

There’s a large group of Spectacled Flying Foxes (fruit bats) that roosts downtown in Cairns as well. They take off at night to feed on fruit, and gather in the roost tree to sleep during the day.

The below slide show contains more pictures of land-based wildlife I took while I was in Cairns:

Below are photos of shorebirds and other water birds. The pictures are primarily from the Cairns Esplanade, but there are a few lakes at the botanic gardens that have a lot of birds around them. If you are in the Cairns area and like birds, you can’t go wrong by spending some time at the Esplanade. There are numerous shorebirds along the beach (especially in the early morning), and birds are abundant in the woodsy parks in the area as well. I managed to spend most of the day there, wandering around watching the birds.

Photos from Kakadu National Park

Here are a few slideshows of photos I took while I was in Kakadu National Park in northern Australia in September 2017.

This first slideshow contains photos I took at the Yellow Water Billabong on a boat ride with Yellow Water Cruises. I took two cruises (one in the late afternoon and one in the early morning), and they were definitely worth it. There is an abundance of bird life around the billabong, and Saltwater Crocodiles were quite common. I also saw a couple of snakes and several Agile Wallabies. A boat cruise is a good way to see waterbirds and reptiles in the park, as it is generally unsafe to hike near water in northern Australia due to the presence of Saltwater Crocodiles. These crocodiles can be aggressive and will attack (and sometimes kill and consume) people. I did go hiking in Kakadu, but avoided going near the water.

Beware of crocodiles!

Click through the slideshow to see the wildlife of the Yellow Water Billabong!

The Asian Water Buffalo in the park are not native and were introduced to the park in the 1880s so they could be hunted. The feral pigs are not native either, and they can unfortunately be quite destructive. Park authorities periodically conduct culls of them, but as they (pigs) are quite fecund, there are still a lot of them around.

The Comb-crested Jacanas display some rather unusual behaviours. Most bird species are monogamous or polygynous (where one male mates with several females). However, jacanas are polyandrous, as females will mate with multiple males, and males incubate the eggs. The young are fairly independent when they hatch, but they do stick around with the male for a while after hatching as he will protect them and guide them to foraging areas.

Magpie Geese also have an unusual mating system. Rather than being strictly monogamous like most geese, breeding trios are common in this species, where one male will pair with two females. The females and male will share the nest and care of the young. I should note that Magpie Geese are in a different family (Anseranatiade) than other geese (which are in the family Anatidae). The Magpie Goose lineage appears to be very old, although only one species remains in the family.

The below slideshow shows pictures I took on various walks in the park. The bush fire pictured was near the town of Jabiru. The Aboriginal people of Australia sometimes intentionally start such bush fires to manage vegetation. This is something they have done for millennia, and it is something they still do. There are numerous reasons for this practice. For example, it can encourage new vegetation growth which attracts grazing animals that can be easily hunted.

Kakadu is also known for its Aboriginal Rock art. Some rock art sites are off-limits to visitors, while other sites are easily accessed and can be viewed by visitors. I took pictures of rock art, as well as the informational signs about it. The Warradjan Cultural Centre in Kakadu has a lot of information on the rock art and other aspects of the culture and history of the Aboriginal people of the region.

Next up will be pictures of birds from Cairns, with a focus on Rainbow Lorikeets. I saw numerous Rainbow Lorikeets in Kakadu, but didn’t get any good pictures.

Red-tailed Black Cockatoos in Kakadu National Park

I have five hours to kill at an airport, so I am updating my blog! Merry Christmas everyone!

Today, I will write about the Red-tailed Black Cockatoos I saw in Kakadu National Park, Australia, in September, 2017. I headed to Australia primarily to go birdwatching and see other wildlife, and my trip covered Cairns, the Cape York Peninsula, and Kakadu National Park. Two black cockatoo species (Black Palms and Red-tailed Blacks) were on my target list of animals to see and I managed to see both. Finding them was extremely thrilling!

Range of the Red-tailed Black Cockatoo. Map based on http://maps.iucnredlist.org/map.html?id=22684744

Red-tailed Black Cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus banskii) are impressive and charismatic birds. They are big (about 60 cm tall), are very loud, and have large, powerful beaks. Like all other black cockatoos, they are extremely rare in aviculture outside of Australia, and as a result the price for a single bird in North America can be very high ($14 000 or more).

Red-tailed Black Cockatoo photographed in Kakadu National Park.

Wild red-tailed blacks have a large and fragmented range in Australia. There are five subspecies: C. b. banksii (Bank’s Red-tailed Black Cockatoo), C. b. macrorhynchus (Northern Red-tailed Black Cockatoo), C. b. samueli (Inland Red-tailed Black Cockatoo), C. b. graptogyne (South-eastern Red-tailed Black Cockatoo) and C. b. naso (Forest Red-tailed Black Cockatoo). The birds I saw in Kakadu were Northern Red-tailed Blacks.

A Northern Red-tailed Black Cockatoo photographed in Kakadu National Park. The lack of bright red in the tail indicates this is a female or a young male.

The various subspecies differ in their foraging habits, beak sizes, female colour patterns, and conservation statuses. Overall, red-tails are not globally endangered and are listed by the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) as “Least Concern.” However, some populations are faring better than others. The South-eastern Red-tailed Black Cockatoo is rare (< 1000 birds exist in the wild) and is considered endangered in Australia. Additionally, Bank’s Red-tailed Black Cockatoos are declining in the southern portion of their range (northern Queensland).

A family group of Red-tailed Black Cockatoos foraging in Kakadu National Park.

Adult male and female red-tailed blacks can be differentiated based on their tail colours: males have bright red panels on their tails while females have orange or pale yellow-orange stripes on their tails. Males younger than about four years look like females. The birds pictured above appeared to be an adult male and female with their offspring. I often saw red-tailed blacks in Kakadu in groups of three, which were most likely to be a breeding pair and their offspring. Red-tails usually only fledge one chick each time they breed, although two is a possibility. Even when I found a loose flock of about thirty or forty red-tails in a grove of trees, many birds were perched together in groups of three (see photo below).

Three Red-tailed Black Cockatoos. An adult male (note the solid red in the tail) is on the left.

Red-tailed Black Cockatoos were common in Kakadu. They seemed to be comfortable foraging or resting up in trees, as well as foraging on the ground. I saw a few groups foraging on the ground in recently-burned forests (maybe they like toasted seeds?). Most birds I saw were present as pairs, trios, or in small flocks of up to ~40 birds. Active birds were generally quite loud and called frequently, so they were hard to miss. However, birds resting in trees were fairly quiet. Although the flocks of red-tails I saw weren’t huge, flocks can at times contain hundreds of birds, especially where food is abundant (such as at peanut farm plantations).

A Red-tailed Black Cockatoo foraging in a recently-burned open forest.

Male (left) and Female (right) Red-tailed Black Cockatoos seen in Kakadu National Park.

During the hottest part of the day (it got to 40 C while I was in Kakadu), Red-tailed Black Cockatoos spend a lot of time resting in trees. I certainly couldn’t blame them – some birds I saw were panting and clearing feeling the heat. I also saw several red-tailed blacks drinking from a muddy, shallow billabong during the middle of the day. It was the dry season when I visited Kakadu, and most groups of cockatoos I found were close to a water source.

Three Red-tailed Black Cockatoos getting a drink of water.

Overall, I saw three cockatoo species in Kakadu: Sulphur-crested Cockatoos, Red-tailed Black Cockatoos, and Bare-eyed Cockatoos. Galahs (Rose-breasted Cockatoos) also occur in Kakadu, although I didn’t see any while I was there. I did, however, see a large flock of them at the Musgrave Roadhouse, on the Cape York Peninsula.

Galahs (Rose-breasted Cockatoos) photographed near the Musgrave Roadhouse in northeastern Australia.

Galahs in the Musgrave area of northeastern Australia.

I will share more of my wildlife photos from Kakadu in my next post. If you’d like more information on Red-tailed Black Cockatoos, please see the below links:

More Information

Conservation of South-eastern red-tailed black-cockatoo Calyptorhynchus banksii graptogyne

Red-tailed Black Cockatoo Recovery Plan

Red-tailed Black Cockatoo Information from the World Parrot Trust

Recordings of Red-tailed Black Cockatoos

A Rose-crowned Conure

As I mentioned in a recent blog post, I got a new parrot in December, 2015. He’s a four-year-old Rose-crowned Conure, a species that is somewhat uncommon in North America. His name is Patrick Perry, although my husband and I usually call him by his nickname “Dip.”

Dip, the Rose-crowned Conure

Rose-crowned Conures are in the genus Pyrrhura (Pyrrhura rhodocephala), and are thus closely related to Green-cheeked and Maroon-bellied Conures. Rose crowns differ in appearance from the most common Pyrrhuras found as pets as they don’t have any tan or grey feathers on the breast and they have white beaks. They are largely green with a red cap on the head, red cheeks, a red tail, and some red feathers on the chest and belly. Their flight feathers are blue (although Dip has a few white primary flight feathers) and they have white primary coverts, which can be seen on the bend of the wing when the bird is at rest (see picture below).

Dip at a parrot show. This picture shows his white primary covers (at the top of the wing). It also shows his three white primary flight feathers, which are supposed to be blue. I’m not sure why he has those white feathers, as he’s healthy and eats a healthful diet.

Juvenile Rose-crowned Conures frequently have less red on the head than adults. Some books on wild birds state that juveniles lack red on the head or have very little of it there (e.g. Forshaw 2010); however, many captive-bred juveniles have quite a bit of red on the head. Juveniles may also have some bluish feathers on the crown and blue (instead of white) primary coverts.

Because Rose-crowned Conures are uncommon in captivity in Canada, Dip is often mistaken for other species. He is most frequently thought to be a Cherry-headed Conure (Psittacara erythrogenys), as both species are red and green with white beaks. However, the Rose-crowned Conure is smaller and has some red on the chest that the cherry heads lack.

The Rose-crowned Conure (AKA Rose-crowned Parakeet) has a rather small range in the wild and is the only Pyrrhura species found in its range. They occur in forested montane areas of northwestern Venezuela (see map below) at elevations of 800 – 3400 m (although they are most common at 1500 – 2500 m). Because they appear to be common in their range, the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) lists them as a species of “Least Concern,” meaning that they do not appear to be endangered or at risk of becoming endangered. However, there is little data available on this species’ population status or behavior in the wild.

The range of the Rose-crowned Conure (shown in orange). Image from: http://www.iucnredlist.org

In the wild and outside of the breeding season, Rose-crowned Conures occur in flocks of approximately 10 to 30 birds, although many small flocks may congregate together at sleeping roosts during the evening. Most breeding parrots stay in pairs during the breeding season; however, one species of Pyrrhura (the El Oro Conure, Pyrrhua orcesi) has a cooperative breeding system, where a breeding pairs’ relatives (or occasionally unrelated birds) may help them with raising young. The ‘helper’ birds in El Oro Conures will feed the breeding pair’s chicks. However, there is little information available on the breeding behavior of Rose-crowned Conures in the wild so I cannot say if they breed as pairs or if pairs receive help from other birds.

Pyrrhuras are often said to be among the more quiet parrot types. Certainly, Dip is nowhere near as loud as my Lesser Sulphur-crested Cockatoo, Blue and Gold Macaw, or Red-lored Amazon. He does make some noise though. He gives off a lot of typical parrot squawks, and he is a very talented whistler. He is also quite talented at mimicking the other parrots. For example, Chiku, my Green-cheeked Conure mix, often says his name and Dip can mimic that perfectly. If I hear “Chiku! Chiku!” sounds from the bird room, I generally cannot tell if it’s Dip or Chiku (or both) making them. Dip can also mimic some of the quieter sounds that Ripley (my Red-lored Amazon) makes.

Dip eats Tropican pellets supplemented with some fresh foods. He particularly enjoys corn, peas, berries, sunflower seeds, and walnuts. I got to pick a lot of wild blueberries this summer and he particularly enjoyed those.

Dip is a very active parrot who loves to climb and chew on wood and cardboard. He lacked a tail when I got him, and his flight feathers were quite short. However, his tail grew back and his flight feathers have molted out and grown back. He likes to fly and his favourite landing spot appears to be the top of my head.

*Do you have a Rose-crowned Conure? Tell me about him/her in the comments!

References

BirdLife International. 2012. Pyrrhura rhodocephala. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T22685877A39028964. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22685877A39028964.en. Downloaded on 02 October 2016.

Forshaw, J. M. 1977. Parrots of the World. T. F. H. Publications: Neptune, NJ.

Forshaw, J. M. 2010. Parrots of the World. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Juniper, T., and Parr, M. 1998. Parrots: A Guide to Parrots of the World. Yale University Press: New Haven, CT.

Klauke, N., Segelbacher, G., and Schaefer, H. M. 2013. Reproductive success depends on the quality of helpers in the endangered, cooperative El Oro Parakeet (Pyrrhura orcesi). Molecular Ecology 22:2011-2027.

Low, R. 2013. Pyrrhura Parakeets (Conures): Aviculture, Natural History, Conservation. INSiGNIS Publications: Mansfield, Notts, UK.

Fascinating Feathers – Structure, Function and Care

Feather Construction

Feathers are composed primarily of a protein called beta (β) keratin. Keratin proteins are found in the skin, scales, and hair of many animals. However, there are structural variations among different types of keratin. The β keratin molecules found in bird feathers are shaped like pleated sheets while the alpha (α) keratin molecules found in mammal skin and hair are helix (spiral) shaped. However, bird β keratin is quite similar to the β keratin found in reptile skin. β keratin is also found in bird claws, scales, and beaks, but the β keratin found in feathers is more elastic than other types of β keratin.

Mature feathers lack a blood supply and are therefore ‘dead’ structures that cannot be naturally repaired if damaged. Newly-growing feathers, however, are living structures with a blood supply, and as such are sometimes referred to as “blood feathers.” However, as a growing feather matures, the blood supply in it will start to recede. In large, shed parrot feathers, it is frequently possible to see remnants of the blood vessels that supplied the feather with blood as it was growing. These remnants (called ‘pulp caps’) will be present as thin bands that stretch across the inside of the hollow shaft of the feather.

New, growing feathers are coated in a waxy sheath that will flake off as the feather matures. Birds remove these sheaths by preening, but because birds cannot preen their own heads, single birds that do not have a partner to preen them may retain the sheaths on their head feathers a little longer than normal. Many parrot owners will preen pin feathers on their birds’ heads, but only do this when the sheaths are dry and flake off easily.

The bands seen in the quill of this Blue and Gold Macaw feather are called “pulp caps.” They are the remnants of the blood vessels that supplied the feather with nutrients while it was growing.

As feathers can become worn through daily wear and tear, they are molted and regrown at periodic intervals. As parrots kept in captivity will experience different patterns of light and dark and may be fed different diets, the timing of the molt can vary among captive parrots. A parrot that has not undergone a molt for a long time (i.e. over a year) may have quite a bit of damage on the tips of its feathers. There may also be some black or brownish marks on the feathers, especially at the tips.

As feathers are made primarily of protein, parrots need sufficient protein in their diets to grow strong, healthy feathers. Pelleted diets generally contain sufficient protein (and amino acids), as can mixtures of grains, cooked beans, peas, quinoa and corn.

Feather Types

Contour Feathers

Most of the feathers that are visible on an adult parrot are contour feathers. These include the tail feathers (also called “remiges”), the flight feathers (also called “retrices”), and the outer (visible and usually coloured) feathers on the head and body. The contour feathers have several functions. The flight feathers allow the bird to fly and the tail feathers help the bird control its flight path. Contour feathers also provide some insulation and waterproofing, protect the body from dust and debris, and can play an important role in communication. For example, cockatoos have erectile crests on their heads that they can raise and lower in order to express anger, surprise, or excitement. Hawk-headed parrots also have a ‘headdress’ of feathers on their heads they can erect. Even parrots without such specialized feathers can erect the contour feathers on their heads and napes if agitated or alarmed. Additionally, many parrots will fan out their tail feathers if alarmed or excited.

Contour feathers are the most structurally complex feathers on a parrot. They are composed of a long, central shaft that has a flat ‘vane’ on either side, except at the base. The base of the central shaft is hollow and will lack a vane. This part of the shaft is called the ‘calamus.’ The upper part of the central shaft, which has a vane on both sides, is called the rachis.

If you take a shed feather and pull the vane apart, you will see that there are many thin, hair-like structures branching off of the rachis. These are called barbs. Many contour feathers have two types of barbs, which are called plumulaceous barbs and pennaceous barbs. Plumulaceous barbs are located near the base of the feather and are white, loose, and soft. Some flight feathers have few or no plumulaceous barbs. Pennaceous barbs are located above the plumulaceous barbs and are firmer. In the pictures of blue and gold macaw feathers accompanying this article, the pennaceous bars are blue.

Blue and Gold Macaw body contour feathers. The fluffy barbs at the base are called plumulaceous barbs and the stiffer blue ones are called pennaceous barbs.

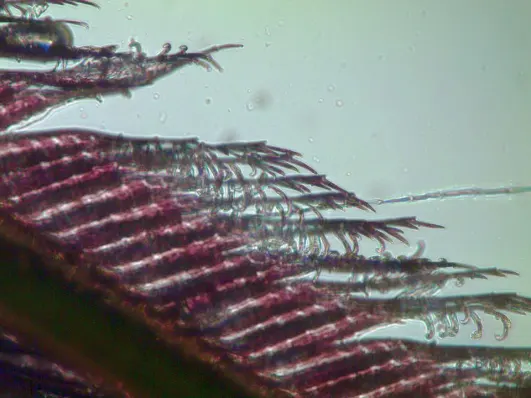

The structure of pennaceous barbs is quite complex. Each barb will have a central shaft called a ramus. Each ramus will then have two rows of structures branching off of them called barbules. These will appear as ‘fuzz’ on the ramus to the naked eye. The ends of the barbules on one side may be covered in little hooks called barbicels. The barbicels can neatly wrap around the barbules on the barbs above. When all of these little hooks are wrapped around the barbules above them, the feather will have a very smooth and neat appearance. However, when a bird goes about its daily activities, the hooks can become dislodged from the barbules.

Above: The ramus of a Red-lored Amazon flight feather, as seen under a light microscope. It has numerous barbules branching off of it, the tips of which are covered in barbicels (the hook-like structures)

Birds can restore the structure of their feathers by preening. When preening, a bird will run his feathers through his beak and this will rehook the barbs on the feathers back together. You can try this with a shed contour feather – pull the barbs apart and see if you can “zip” them back together with your fingers.

Remiges and Retrices

The remiges (tail feathers) and retrices (flight feathers) are the largest and stiffest feathers on a parrot and they provide little insulation but are critical for flight. They differ from other feathers in that they are generally attached to bones, instead of being anchored in the skin.

The primary flight feathers (the flight feathers at the end of the wing) provide forward thrust when a bird flaps its wings downward. These feathers are attached to a bird’s manus (‘hand’) bones and the bones of its second digit. Parrots have ten primary feathers. The secondary flight feathers are also critical for flight and they help provide a great deal of lift. These feathers attach to the ulna (“arm bone”) of the wing. Most parrots will have ten secondary feathers but this number varies from 8-14.

The primary and secondary flight feathers differ from contour feathers on the body in being asymmetrical, as the leading vane will be narrower than the trailing vane. Both primaries and secondaries are asymmetrical, but the primary flight feathers are typically longer and more pointed than the secondary flight feathers.

Parrots have twelve retrices (tail flight feathers), which also have asymmetrical vanes. The central retrices are attached to the tail bone (pygostyle). Tail feathers play an important role in steering and braking.

Down Feathers

Underneath the contour feathers are down feathers. They provide lightweight and effective insulation and they are white and have a simpler structure than contour feathers. They either lack a central rachis, or have a very short one. If there is a rachis, the barbs will be much longer than it. The barbs can have small projections on them, but they do not hook together the way pennaceous barbs on a contour feather can.

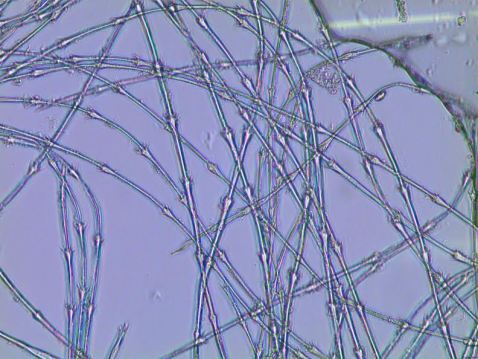

A down feather from a Lesser Sulphur-crested Cockatoo, as seen under a microscope.

Cockatoos, African gray parrots, and Mealy Amazons also produce large numbers of specialized down feathers called powder down feathers. A few other groups of birds, including herons, also produce powder down feathers. The barbs of powder down feathers slowly disintegrate over time and produce a white talcum-like powder that will coat the bird’s feathers. Unlike other types of feather, powder down feathers grow continuously and are not molted.

Semiplumes

There are feathers that appear to be intermediate between a down and a contour feather. These are called semiplumes. Unlike down feathers, they have a central rachis, but the barbs are white and fluffy, like the barbs on down feathers. They are usually hidden underneath the surface contour feathers and likely help with insulation.

Filoplumes and Bristles

Filoplumes are inconspicuous feathers that are hard to see and are somewhat hair-like in appearance. They are composed of a central shaft with a few short barbs at the top. They are associated with contour feathers, especially those on the wings and tail. They have a sensory function and monitor the movements of the contour feathers. When feathers associated with filoplumes move, the filoplumes move too. Because filoplumes have many sensory cells at their bases, their movement allows the bird to sense movement in his feathers.

Bristles are also simple in structure. They are short and have a central shaft with a few barbs at the base. On parrots, they are often located around the eye and nostrils where they presumably have a protective function and keep debris out.

Preening and the Preen Gland

Parrots spend a lot of time preening their feathers in order to keep them smooth and clean. A small gland just above the base of the tail also plays an important role in preening. This gland (the uropygial, or “preen” gland) secretes a mixture of chemicals, including waxes, fatty acids, fat, and water. When parrots preen, they often nibble at the preen gland (to get preen gland oil on the beak) and then rub their beaks along their feathers. That applies the preen gland oil to the feathers. They may also rub their heads against the gland and then rub their heads on the feathers.

It is not completely clear what the function of preen gland oil is (particularly in parrots), although it generally appears to help with waterproofing feathers and maintaining their elasticity. In addition, the preen gland oil of chickens contains vitamin D precursors, and many books and articles on birds state that when ultraviolet light hits these precursors after they are spread on feathers, they are converted to vitamin D, which the bird can then ingest as it preens. Thus, preen gland oil may provide a vitamin D supplement. However, some parrots, including Amazons and Hyacinth Macaws, lack preen glands but do not generally suffer from vitamin D deficiencies.

Parrots preen themselves to maintain the integrity of their feathers, and they also need baths or showers to keep their feathers clean and healthy. Some birds prefer showers, and such birds should be sprayed with water a few times per week. Others may prefer to bath, and such birds should be offered bowls of water for bathing purposes. If a parrot really enjoys water, it’s fine to bath or shower him or her every day if desired.

Conclusion

World Parrot Refuge Closes

The World Parrot Refuge was a parrot shelter located on Vancouver Island, which is off of Canada’s west coast. It was always intended as the final ‘home for life’ for parrots taken there, as no parrots were ever adopted out of the facility. Approximately 900 parrots of all sizes lived at the refuge at one point.

This way of running a parrot refuge was quite controversial. I’d never been there, but some people I know who had been there felt bad for the parrots who seemed to crave human attention. Leaving mixed species together in a flock (as was done at the refuge) can also result in some birds being picked on or attacked by others. Personally, I don’t doubt the good intentions of the Refuge founder, but the whole enterprise seemed unsustainable to me.

The founder of the facility unfortunately passed away in February, 2016 and the refuge ran into serious financial problems. Shortly after that, the landlord of the facility gave them a date of August 1 to find a new place.

A recent article in the Parksville-Qualicum News (click the link to go to the article) notes that there are no longer any birds at the World Parrot Refuge and that they are at various facilities in British Columbia. The Greyhaven Exotic Bird Sanctuary played a large role in rescuing the parrots and finding them somewhere to go.

If you would like to help with this rescue effort, please check out ways you can help by going to the Greyhaven Website. They are caring for almost 600 of the World Parrot Refuge birds and it is a very expensive undertaking! I’m sure any amount of money you could donate would be appreciated.

LINKS TO MORE INFORMATION:

Huge Public Response to BC ‘parrot disaster.’

Greyhaven Bird Sanctuary Struggles to Care for over 500 Relocated Parrots

Hundreds of Parrots and Cockatoos Ready for Adoption in British Columbia